West Ham suspend transfer director after he claims African players ’cause mayhem’

West Ham director of player recruitment Tony Henry has been suspended “pending...

Racism is not the reason the Real Madrid striker is out of Euro 2016 – but France has a real problem with religion and race

Karim Benzema made his claim loud and clear: he believes that Islamophobes and racists have lobbied to stop him from playing for the national side during Euro 2016.

“[Didier] Deschamps has ceded to racial pressure in France,” the Real Madrid striker toldMarca. “He must know that an extreme right party has reached the second round of the latest elections.”

Benzema is referring to the Front National, which has made huge gains in recent years, often capitalising on anti-immigrant sentiment, particularly against Muslims.

That sentiment has snowballed since the two horrific terror attacks in Paris last year – first at the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January, and then the acts of mass murder on Friday, November 13 which represented an unprecedented strike against the French way of life – a “change of paradigm” as terrorism expert Jean-Charles Brisard told the LA Times.

However, Benzema’s specific claims appear to be without merit. France coach Deschamps has picked several Muslim players for the Euros, including Adil Rami, who like Benzema is of North African descent. Meanwhile, 28-year-old Benzema is under investigation for the charge of conspiracy to blackmail international team-mate Mathieu Valbuena.

That is a serious allegation which has lingered since late 2015. It is not his first criminal charge, either. Benzema’s ‘deselection’ must be attributed to his legal troubles as he had started matches under Deschamps prior to the claim that some of his associates were using a sex tape to extort money from Valbuena.

Former Arsenal midfielder Emmanuel Petit told L’Equipe that Benzema’s declaration was “putting oil on the fire” of an already tense political situation. But others are not so sure – the catalyst was comments made by the notoriously outspoken former Manchester United star Eric Cantona in an interview with the Guardian.

The arch polemicist, it should be stressed, has had a long-running feud with Deschamps that stretches back over two decades and resulted in the ex-Juventus man being branded a “water carrier” and a player who could be found “on every street corner”.

On this occasion, though, the accusations were darker.

“Benzema is a great player. [Hatem] Ben Arfa is a great player. But Deschamps, he has a really French name. Maybe he is the only one in France to have a truly French name. Nobody in his family mixed with anybody, you know. Like the Mormons in America,” Cantona said, pinpointing the players of North African origin who had been overlooked for Les Bleus’ Euro 2016 squad.

However, Ben Arfa has set the example for Benzema. An outcast at Newcastle and out of work for six months, the attacker has propelled himself back onto the fringes of the national scene with a quite outstanding season with Nice. He is a player now loved in France, not only for his talents but for his desire to get back to the top, having been cast as an enfant terrible for much of his career.

Ben Arfa has not quite made the cut, but he is on standby. Given he fell out with Deschamps spectacularly while with Marseille, it speaks volumes for the quality of his play this season that he has been able to work his way back into contention in any manner at all. Deschamps can scarcely be blamed for overlooking him when both Anthony Martial and Kingsley Coman have been superb for Manchester United and Bayern Munich, respectively, at an unquestionably higher level. And if an attacking player picks up an injury, Ben Arfa – whose career was considered over last summer – is in pole position to make a remarkable return to international football.

Asked if Deschamps, who has promised to sue Cantona for his remarks, is a racist, Benzema replied: “I don’t think so,” but the implications of Cantona’s original quotes are less clear.

While Benzema and Cantona’s comments may be without merit, the claims have re-opened a festering wound in French football and society.

Official figures showed that there was a rise of 300 per cent in incidents of an Islamophobic nature in France in the first half of 2015 (up to 400), which has been attributed to the Charlie Hebdo attacks.

The Central Council of Muslims of France, however, suggest that 15% of incidents never get reported to the police due to a feeling that they will simply be ignored. The statistics have not yet been compiled to reflect Islamophobic activity following the wider Paris attacks in November.

France’s history as a colonial power in North Africa has ensured that it has had a difficult relationship with the region for close to two centuries. But previous attacks on the country were previously driven by nationalistic causes and not ‘religion’. Things have changed in recent years.

The rise of Islam in the banlieues (suburbs) of France’s big cities in the 1990s has had a profound effect on the nation’s footballers. These areas have traditionally been a hotbed of talent; Zinedine Zidane was born in La Castallane in Marseille, one of the most notorious districts in Europe, while Benzema himself grew up in a disadvantaged corner of Lyon.

Hastily erected in the 1960s, the banlieues are disproportionately populated by immigrants, for whom they were constructed, but a lack of adequate social infrastructure and planning means that they are areas of grave deprivation.

Surrounded by communities of often traditional families, finding a cultural identity can be challenging for youths due to the state’s policies of assimilation, which encourage immigrants to become ‘French’ by losing societal identities, such as religion or race.

High youth unemployment (those under the age of 25) in France – hovering around 25% for several years, according to the European Commission – can reach up to 50% in the banlieues, which are powder-kegs for residents of all backgrounds.

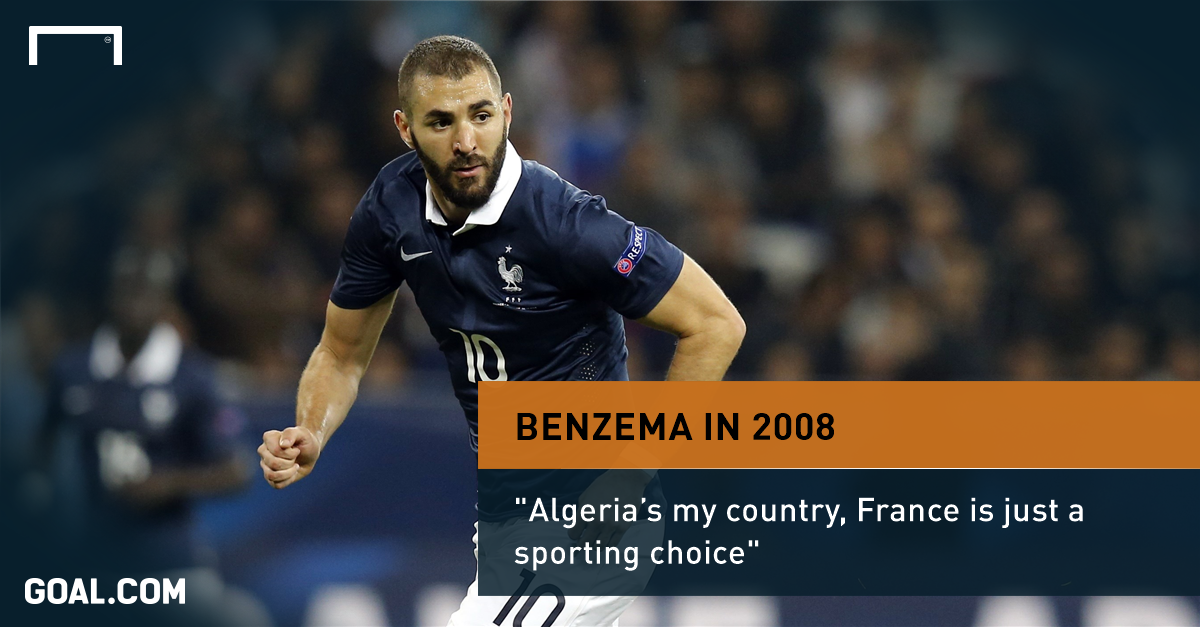

As such, some French-born youths may reject their nationality. Some born to non-immigrant families even convert religion and adopt the culture of their locale. “Algeria’s my country, France is just a sporting choice,” Benzema bluntly told RMC in 2008, highlighting the difficult dichotomy that dual citizens have to juggle. It is a statement that has echoed around the media ceaselessly since his latest comments.

By the early years of the new millennium, Paris Saint-Germain’s youth ranks boasted a majority of Muslim players – including Liverpool’s Mamadou Sakho, who joined the club in 2002.

Clubs have consequently been posed fresh challenges. Among the more banal has been structuring training effectively around the fasting holiday of Ramadan.

Integration has, therefore, proven a thorny issue, particularly at lower levels of the game, where teams are often organised around neighbourhood and ethnic groups, contradicting the state’s desire for assimilation.

Nevertheless, overt evidence of Islamophobia within the French game is difficult to find. But is not unknown. In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Salim Baghdad, at that time on the books of Nancy, was the victim of a frightening episode.

“I’m the collateral damage of what happened at Charlie Hebdo,” he explained to France Football.

Baghdad was stopped outside in his car after training in January by someone purporting to be a supporter.

“He was kidding with me that we had to win promotion to Ligue 1,” Baghdad said. “Suddenly, he spat on me and began to insult me: ‘Dirty Arab, foreign scum, we are all Charlie, France is for the French.’”

As three other men approached his car, he sped away home to discover his wife in tears.

“She told me all afternoon that people knocked at the door,” he continued. “They left a bag at the door. I looked inside and there was a note that read: ‘Salim Baghdad, born September 11, went to the same high school as Mohamed Merah’, but there was also pork and a French flag.”

Merah, who was referenced in the note to Baghdad, killed seven people in 2012, including five at a Jewish school, after an eight-day anti-Semitic shooting spree in Toulouse and Montauban.

The player only went to the press after speaking to veteran Morocco striker Youssouf Hadji, as Nancy boss Pablo Correa advised him to stay quiet over the story. “He told me: ‘You must not talk about it, it could explode, plus the political climate is tense in France,’” Baghdad, who now plays in Algeria with RC Arbaa claimed.

Benzema’s claims are less personal and more societal, yet fail to take into account his unique circumstances.

For years he has been urged to resist the company of his childhood friends from the banlieue. A report in Spain from AS said that Barcelona elected against signing the Frenchman as far back as 2008 due to those he surrounded himself with; two years later, shortly before the World Cup, he was accused, though later acquitted, of soliciting an underage prostitute.

Euro 2016 should have been the biggest event of his career, but now Benzema finds himself under investigation for another crime – one that is associated with those people he should have rejected a decade ago. This is not a question of faith or ethnic background, but loyalties to old friends. Countless such examples can be found across sports, many of which are far more serious – former NFL star Aaron Hernandez is serving life without parole for a gangland murder.

When French Prime Minister Manuel Valls voiced his opinion that Deschamps should not select Benzema as the striker was not of the moral stature to represent the country, the Madrid striker hit back on Twitter.

“Twelve seasons I’ve been a professional: 541 matches, 0 red cards, 11 yellow cards!!! And certain people say I’m not exemplary???” he fumed.

12 saisons que je suis professionnel : 541 matchs joués 0 carton rouge 11 cartons jaune !!! Et certains parle de mon exemplarité ???

— Karim Benzema (@Benzema) March 15, 2016

But goals and yellow cards are not a mark of morality. On the field, there is no doubt that Benzema is France’s top centre forward. Off it, however, his comportment is certainly questionable, particularly in relation to the current charge – one involving an international team-mate (who incidentally also failed to make Deschamps’ squad) hanging over his head.

Islamophobia is not the reason Benzema will not play at Euro 2016 – or perhaps ever again for Les Bleus given his most recent outburst. The backlash from Benzema’s comments has been remarkable – from both sides of the political divide.

Front National MP Marion Marechal-Le Pen was typically quick to pounce, stating on Twitter: “Born and raised in our country, Benzema has become a multi-millionaire thanks to a France upon which he spits today.

“Let him play for ‘his country’ if he is not happy.”

Né et formé dans notre pays, #Benzema est devenu multi-millionnaire grâce à une France sur laquelle il crache aujourd'hui. Indigne.

— Marion Le Pen (@Marion_M_Le_Pen) June 1, 2016

#Benzema : "L'Algérie c'est mon pays la France c'est juste pour le coté sportif". Qu'il aille jouer dans "son pays" s'il n'est pas content !

— Marion Le Pen (@Marion_M_Le_Pen) June 1, 2016

While her motivations are questionable, Socialist Party MP Benoit Hamon told Europe 1: “Benzema is right to say that we are in a country where racism is increasing. Deschamps is not racist and I know to the contrary Le Graet isn’t either, but there’s an unhealthy climate in the country on these matters. It’s a climate that leads many French to choose a scapegoat, and they always, always have the same head.”

Mourad Boudjellal, president of top European rugby club Toulon, has spoken out vehemently against Benzema’s remarks.

“I think that against the backdrop of disappointment, Benzema has made comments that are dangerous these days,” he told L’Equipe. “He didn’t measure the danger of his words. Unless he wants to become a goodwill recruiter for IS, he must do things differently.

“He could become a great example to some of their recruiters, to tell young people: ‘Well look, even if you become the best in your sport, like Benzema is at football, you’ll be rejected, you won’t be picked for France.”

Like Benzema, comic book entrepreneur Boudjellal is of Algerian descent. Like Benzema, he grew up in a poor neighbourhood, the son of a taxi driver. He has been the victim of racism and is an outspoken opponent of the Front National, which is popular in Toulon. He even cancelled Toulon’s friendly match against Beziers in 2014, because the town had elected a Front National mayor.